The appearance of disappearance: the CIA’s secret black sites

Photographer Edmund Clark and journalist Crofton Black on the CIA’s covert detention facilities

The windowless warehouse built by the CIA in Antaviliai, a quiet hamlet surrounded by lakes and woods, 20km from the Lithuanian capital, Vilnius; photographed in 2011. Work began on the prison facility in 2004. By the time of its closure, in March 2006, the existence of the CIA’s secret detention programme had been widely publicised, although not yet officially acknowledged.

Twelve years ago, in a village on the edge of a pine forest not far from Lithuania’s elegant capital Vilnius, workmen constructed an unusual warehouse. It was the size of an Olympic swimming pool with no windows, many air vents and no stated purpose. The site had formerly been a riding stables and a paddock. It had also served as a local watering hole — a welcome one since the village lacked a bar or restaurant. The new building was shiny and modern, incongruous amid the tumbledown farm buildings and Soviet-era housing blocks. The convivial atmosphere of the riding club was replaced, in the words of one local inhabitant, by “this certain emptiness”.

Naturally, the neighbours were curious. They speculated about the new building’s function. Was it a military listening post? A drug factory? A clandestine organ transplant lab? None of them guessed that it might be a key facility in the US Central Intelligence Agency’s Rendition, Detention and Interrogation programme, one of a secret network of “black sites”, set up in half a dozen countries to house undisclosed prisoners out of reach of lawyers, the Red Cross or other branches of the US government. Why should they? Lithuania was a long way from the front lines of the war on terror, and the village of Antaviliai, although only 20 minutes by car from the capital, was known for summer lake swims rather than for covert operations.

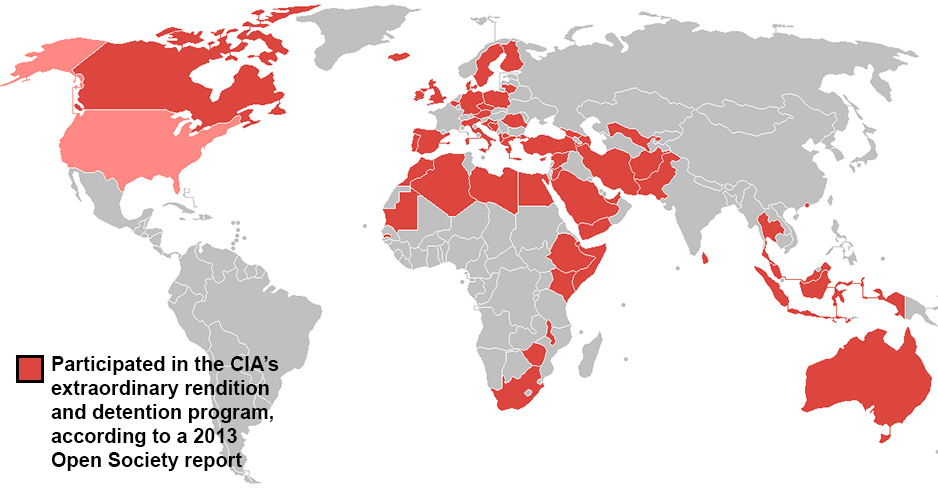

The secret detention programme, as it was gradually uncovered, stretched across the globe. The network of sites we have documented encompasses Antaviliai and Kabul, North Carolina and Skopje, Columbia County, Milan, Tripoli and Bucharest. In our journeys through this material, we have sought to portray the appearance of disappearance.

Sceptics like to invoke the power of photography, its ability to show what is real. Three years ago, at a hearing for a European Parliament civil liberties committee inquiry into complicity in illegal detentions, one MEP asked if he could see a photograph of a prisoner on a plane. Failing that, he would remain convinced of the fictional world in which it didn’t happen. In the same way, Valdas Adamkus, a former president of Lithuania, when asked during a visit to London in 2011 about CIA prisoners being held in his country, stated firmly that: “Nobody proved it, nobody showed it.”

In unveiling the form and structure of the network, journalists and investigators pieced together elements in many countries. Police identified names of rendition crews from phone and hotel records. We compiled dossiers with material accumulated from plane movements, government archives, NGO and media investigations, contractual paperwork and invoices. A summary of a 6,000-page report by the US Senate Intelligence Committee, partially and belatedly released in 2014, confirmed much that had by then already become public, but held a fig leaf over the names of participating countries. Last year, US government lawyers, long loath to admit to the programme’s existence, admitted to the existence of 14,000 photographs of prisoners being transported on planes and held in secret locations. Nonetheless, across Europe, officials still deny that there is any evidence of their countries’ involvement with the secret detention network.

Macedonia. The room in the Skopski Merak hotel where Khaled el-Masri was held by Macedonian officials in January 2004; May 2015. Khaled el-Masri was detained by Macedonian police, who confused his name with that of an al-Qaeda suspect and handed him over to the CIA. He was held in a secret prison in Afghanistan for four months before the CIA acknowledged its mistake. He later sued CIA director George Tenet for imprisonment and torture but the US dismissed the case under state secrets privilege. He later won a case for compensation in the European Court

So far, the Obama administration has refused to disclose its 14,000 photographs, and as a result we cannot show them. We can show, however, a swimming pool in a hotel in Mallorca where a flight crew relaxed for a couple of days between dropping off one piece of human cargo and picking up another. We can show a bed in a hotel room in Macedonia, where a man was tied up for 23 days before being flown to a facility in Afghanistan because he had the same name as someone else. We can show the bland fronts of offices, large and small, where the transport was organised. We can show paperwork linking a multinational service provider — a blue-chip company with thousands of employees that was formerly a contractor for Transport for London — to an aviation brokerage, a mom-and-pop affair in upstate New York. And we can show documents from the court case that ensued when two logistics firms fell out over how many hours had been flown and how much money had been earned — documents that, on close inspection, laid out the history and blueprint of the US’s most secret post-9/11 government programme.

A page from the CIA’s Special Review: Counterterrorism Detention and Interrogation Activities (September 2001-October 2003), dated May 7 2004. In 2004, after complaints by government officials, the CIA’s inspector-general conducted a review of the first two years of the agency’s detention and interrogation activities. It examined the range of ‘enhanced interrogation techniques’, including ways in which interrogators had exceeded authorised methods. Much of the report was redacted on its eventual declassification and publication in 2009

El-Masri’s sketch of the layout of the hotel room during his detention. (El-Masri vs Tenet, Court of Appeals for Fourth Circuit, Exhibit F)

. . .

Looking for meaning in unexpected areas began with the weak points of business accountability: the traceable bureaucracy of invoices, documents of incorporation and billing reconciliations from companies using the familiar paths and carriages of executive travel and global exchange. These pieces of paper bear the traces of small- and medium-enterprise America seeking profit from the outsourcing of prisoner transportation. The documents and the locations to which they refer are the everyday façades behind which global, public-private partnership operated. The photographs show only banal surfaces, unremarkable streets, furnishings, ornaments and detritus. Look at them and they reveal nothing. Look into them and they are charged with significance. They are veneers of the everyday under which the purveyors of detention and interrogation operated in plain sight.

The process of investigating these events proceeds in a puzzling order: revelations are veiled, significance emerges in retrospect, the central shifts to the peripheral, paradoxes and contradictions solidify and dissolve. It is an experience that, by turn, sheds light and acknowledges impenetrability. The act of photographing becomes not one of witnessing but an act of testimony, recreating parts of this network.

Mallorca. Swimming pool in the Hotel Gran Meliá Victoria, Palma de Mallorca; September 2014. The rendition team and crew from N313P relaxed in the hotel in January 2004 after the transfers of Binyam Mohamed from Morocco to Afghanistan and of Khaled el-Masri from Macedonia to Afghanistan. Binyam Mohamed was held in Guantánamo Bay between 2004 and 2009, when he was released without charge

In piecing together evidence of rendition, our account includes locations where nothing happened and people who never existed. A flight crew, enjoying a rest and recuperation stop in Palma de Mallorca, travelled under false names with no addresses other than anonymous PO boxes. A plane filed a flight plan for Helsinki but never arrived there, going instead to Lithuania, then recorded its onward destination as Portugal while travelling to Cairo. A company registered in Panama and Washington DC gave power of attorney to a man whose address turned out to be a student dormitory where no one of that name was known. A series of letters, purportedly from the US State Department, accrediting air crew to give “global support to US Embassies worldwide”, were all signed by Terry A Hogan — one name with many differing signatures.

Billing reconciliation document, N308AB, Prime Jet and BaseOps, August 2004. (Document on file with Reprieve) In 2003, Computer Sciences Corporation (CSC), an IT support company, acquired DynCorp Systems and Solutions, a private military company, and with it a government aviation contract to organise flights at short notice for US government personnel. CSC made use of trip-planning companies to take care of arrangements such as overflight permissions, landing and handling fees. Here, trip planner BaseOps invoices operating company Prime Jet for services rendered to its aircraft N308AB between August 23 and August 25 2004. This plane carried black site prisoner Laid Saidi from Afghanistan, where he had been imprisoned by the CIA for 15 months, to Algeria, where he was released without charge

These are all masks, obscuring by design and revealing by accident. The most common form in which the appearance of disappearance is found, however, is the simple black line: the redaction or strikeout. Sometimes this can be applied to entire paragraphs, pages. From these black lines many things can be perceived. Every black line has to hide something.

. . .

While contemplating these abstractions, we should remember that principally what disappeared here is people. They remained disappeared for between half a dozen and 1,600 days, as far as records — eventually released in 2014 by the Senate Intelligence Committee, in a form that was almost entirely redacted but still susceptible to interpretation — can determine. What also disappeared is the law. In the US, Europe, in almost all the world, the law is very clear: no secret detention, no torture. But sometimes the law is a mirage. The law can determine — has determined, indeed — which firm owes how much money to which other firm for performing prisoner transport flights. But who set up and ran the secret prisons, where, how? Who was responsible? Even as the answers become increasingly well attested, these questions remain beyond the law’s vanishing point. The documents and photographs that we have excavated are physical artefacts of extraordinary rendition. At a time when one US president has failed to close the Guantánamo Bay detention camps after two terms, and one of his prospective successors wants to “bring back a hell of a lot worse than waterboarding”, the negative publicity evoked by these images is an indication of how the law vanished.

New York. Richmor Aviation’s office at Columbia County Airport, New York; February 2013. In early 2005, Richmor Aviation’s Gulfstream jet N85VM was publicly implicated in the CIA’s 2003 abduction of the Egyptian cleric Abu Omar from Milan, Italy. A year and a half after the jet’s role was publicised, Richmor’s president Mahlon Richards wrote to aircraft brokerage firm Sportsflight. Despite the re-registration of the plane, it would, he said, ‘always be linked to renditions’. Shortly afterwards he took Sportsflight to court for money owed. In this section of the court transcript, Richards describes how N85VM flew to Italy, Afghanistan, Guantánamo Bay, ‘to every place’. The purpose was to pick up ‘a bad guy’. The court clerk has corrected the misheard ‘theorists’ to ‘terrorists’. The judge agreed with Richmor’s assessment that the context of renditions was ‘irrelevant and immaterial’ to the case. Sportsflight was ordered to compensate Richmor for its lost earnings

Transcript of the cross-examination of Mahlon Richards, Richmor Aviation Inc vs Sportsflight Air Inc, Supreme Court of the State of New York, County of Columbia, Index No 07-2171, July 2 2009

Afghanistan. Site in north-east Kabul, now obscured by new factories and compounds, believed to have been the location of the Salt Pit; October 2013. The Salt Pit is the name commonly given to the CIA’s first prison in Afghanistan, which began operating in September 2002. Dozens of prisoners were held there over the next 18 months. Gul Rahman, a young Afghan detainee, died of hypothermia there in November 2002. He was buried in an unmarked grave. The US Senate’s report on the CIA programme described how detainees ‘were kept in complete darkness and constantly shackled in isolated cells with loud noise or music and only a bucket to use for human waste’. Members of a visiting delegation from the Federal Bureau of Prisons commented that they had ‘never been in a facility where individuals are so sensory deprived’. The site was closed in 2004 and replaced by a purpose-built facility

Sketches by Mohammed Shoroeiya, a Libyan opposed to the Gaddafi regime, of two of the torture devices used on him in a CIA prison in Afghanistan, where he was kept for a year in 2003-04. They show a small wooden box in which he was locked, and a waterboard to which he was strapped. Other drawings showed a narrow windowless box in which he was held naked for one and a half days. According to the US Senate report, Shoroeiya was ‘walked for 15 minutes every half hour through the night and into the morning’ to prevent him from sleeping. He said: ‘They wouldn’t stop until they got some kind of answer from me.’ In August 2004 he was flown by a CIA-contracted jet to Libya, where he was imprisoned. He was finally released in February 2011. (©Mohammed Shoroeiya from Human Rights Watch report, Delivered Into Enemy Hands: US-Led Abuse and Rendition of Opponents to Gaddafi’s Libya, 2012)

‘Negative Publicity: Artefacts of Extraordinary Rendition’, by Edmund Clark and Crofton Black, is published by Aperture/the Magnum Foundation, £50;aperture.org/flowers gallery.com.

The authors will be in conversation with Julian Stallabrass at the Courtauld Institute on Wednesday March 23, admission free; courtauld.ac.uk.

Images from ‘Negative Publicity’ will be included in an exhibition of Edmund Clark’s work at the Imperial War Museum, London, from July 28 2016 to August 28 2017

Photographs: Edmund Clark, Courtesy of Flowers Gallery London and New York

___

http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/2/90796270-ebc3-11e5-888e-2eadd5fbc4a4.html