The servicer says publicly it wants to help you pay debt. In a government lawsuit, it has a different message.

by Shahien Nasiripour

Over the past several years, Jack Remondi, chief executive of student loan giant Navient Corp., has gone out of his way to tout the company’s devotion to helping Americans cope with student debt.

He’s mentioned it in meetings with investors, on calls with Wall Street analysts, in testimony before Congress, and even on his Medium blog. “At Navient, our priority is to help each of our 12 million customers successfully manage their loans in a way that works for their individual circumstances,” he said March 20.

But faced with a potential multi-billion dollar lawsuit by the federal government for not living up to that mantra, Remondi’s company, formerly an arm of student lender Sallie Mae, sang a different tune in court filings.

Borrowers can’t reasonably rely on America’s largest student loan servicer to counsel them about their many options, Navient said on March 24 in a motion to dismiss the case, because its primary role is, after all, to collect their payments.

“There is no expectation that the servicer will act in the interest of the consumer,” Navient said in response to the litigation filed Jan. 18 by the U.S. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

With about one in four of the nation’s roughly 44 million student debtors either in default or struggling to stay current, there’s broad agreement that loan servicers such as Navient are key to ending the crisis. Remondi, 54, has said as much on several occasions. One of his four ideas to slash defaults is for policymakers to encourage borrowers to call their loan servicer. “For some borrowers, student loan debt can be especially daunting. The good news is that borrowers can turn to their student loan servicers for help to navigate the complex repayment options,” Remondi said in February.

But in court, Navient made clear that the company’s main job isn’t helping debtors; it’s getting them to cough up cash for creditors like its biggest client, the U.S. Department of Education. The department, Navient explained, didn’t agree to pay for the level of customer service the CFPB wants Navient to give.

“This ranks among the most appalling statements I have heard in my career,” said David Bergeron, who after more than 30 years of working at the Education Department recently retired as the head of postsecondary education. “If that’s all they are doing,” Bergeron said of Navient’s claim that its only responsibility is to collect, “the Treasury Department and the Internal Revenue Service would do it better.”

“What this means for the Education Department is that it needs to fire Navient,” Bergeron said. “Damn the costs.”

Patricia Christel, a Navient spokeswoman, declined to make Remondi available for an interview. The company helps borrowers “navigate loan repayment through proven solutions,” she said in a prepared statement. In court, Navient has also sought to undercut the lawsuit by arguing that the CFPB—under siege by a Republican-controlled Congress and White House—is itself unconstitutional.

In January, the CFPB sued Navient in a Pennsylvania federal court, alleging the company “systematically” cheated student debtors by taking shortcuts to minimize its own costs. Navient illegally steered struggling borrowers facing long-term hardship into payment plans that temporarily postponed bills, the government alleged, rather than helping them enroll in plans that cap payments relative to their earnings.

The latter option promises debtors the possibility of debt forgiveness after years of steady payment. The former raises the possibility of a financial time-bomb.

Navient chose the former, the CFPB said, because it took less time for its employees to set up. Borrowers can typically enroll in so-called forbearance plans over the phone, while income-based repayment plans require paperwork and lots of explanation.

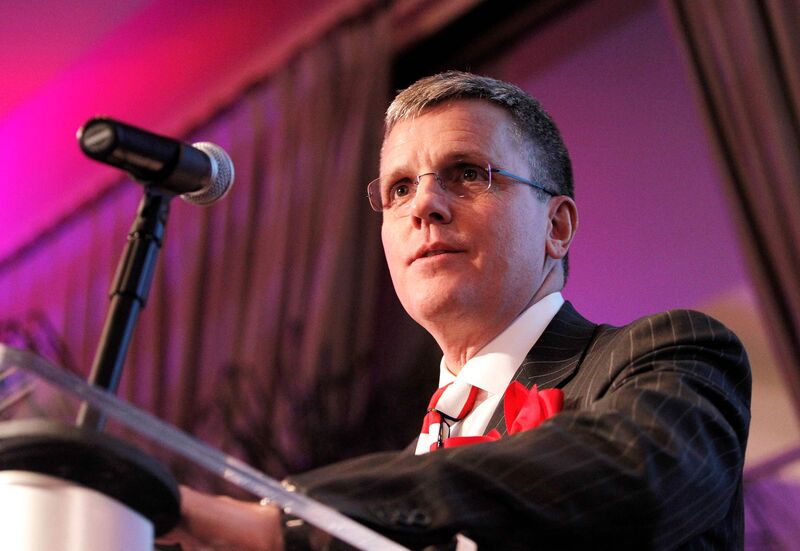

Jack Remondi, president and chief executive of Navient, formerly the servicing arm of Sallie Mae, in 2014 – Photographer: Paul Morigi/AP Images for Reading Is Fundamental

In July 2013, when Navient was the servicing arm of Sallie Mae, Remondi said in an earnings call that “it’s very expensive work, for example, to enroll a borrower into something like an income-based repayment program … which we are doing. But we don’t actually get paid for outperformance in that side of the equation.”

By pushing distressed debtors into forbearance agreements, the CFPB said, Navient’s conduct violated a federal law (PDF) banning “abusive” practices.

The Education Department and Navient repeatedly encouraged borrowers to contact the company if they had trouble meeting their obligations, the CFPB said in its complaint. Through statements on the websites of both the company and the government, debtors were prodded to reach out. But when they did, Navient employees allegedly sought to exploit their lack of knowledge and steer them into payment plans more beneficial to Navient, the CFPB said.

The consumer protection bureau estimates that as much as $4 billion in additional interest charges were added to principal balances of loans repeatedly placed in forbearance. The CFPB seeks an injunction barring such conduct, modification of existing payment agreements, and restitution to affected students.

“The Education Department ultimately is asking loan servicers to act on its behalf to fulfill its fiduciary responsibility to borrowers,” Bergeron said, and the government “expects its servicers to make sure that borrowers gain access to income-based repayment plans.” The CFPB argued in its complaint that this was decidedly not the case with Navient.

Navient has repeatedly denied the government’s allegations, pointing to how more than 40 percent of loan balances it services for the Education Department are enrolled in income-based repayment plans. Borrowers with Navient-serviced federal loans are less likely to default within the first three years of payments than the national average, company spokeswoman Christel argued, citing the company’s internal data.

However, an analysis of the most recent federal figures shows that 30 percent of Navient-serviced borrowers are behind on their payments—the worst rate among the Education Department’s loan contractors. CFPB data also show (PDF) that Navient ranks seventh on a list of the nation’s most recently complained-about financial companies.

In its motion to dismiss the consumer bureau’s complaint (PDF), Navient argued that borrowers couldn’t “reasonably rely” on the company to counsel them about their options, because federal law doesn’t require it. Furthermore, Navient said, its public statements encouraging borrowers to contact the company didn’t mean Navient would act in borrowers’ best interests. Its only legal duty is to lenders, it argued.

“It’s rare for a company to be this bold,” said Jenny Lee, a former CFPB attorney now with the law firm Dorsey & Whitney LLP in Washington. “It’s a sound legal argument, but it may not be the best public relations argument.”

Suzanne Martindale, a San Francisco-based attorney for Consumers Union, the advocacy arm of Consumer Reports, said Navient’s claim raises questions as to whether borrowers are afforded their right to apply for income-based repayment plans. Bergeron, the former Education Department official, and Rohit Chopra, formerly a student loan regulator with the CFPB, added that they couldn’t recall ever hearing—in public or private—a loan servicer arguing that it wasn’t required to counsel borrowers about their options.

“When consumers call their servicers, they’re not expecting them to withhold information,” Chopra said.

If anything, a close review of Navient’s utterances outside of court revealed a consistent message of commitment to helping borrowers manage their student loans.

Last May, for example, Remondi wrote on his blog that “at Navient, we make it a priority to educate our federal borrowers about income-driven options,” because, he explained, the government’s various income-based repayment plans “are our primary tool in helping borrowers avoid default.”

Almost two years earlier, in September 2014, Remondi told investors at a Wall Street conference that the typical borrower doesn’t know the difference between the government’s various income-based repayment plans. “Our job as a servicer,” Remondi explained, “is to really work with those customers and make sure that they understand the differences and which program best fits their needs.”

During the Obama administration, the CFPB urged financial companies to reorient their culture toward a more consumer-focused approach, said Lee, the former CFPB lawyer. “But then there’s a perverse incentive,” she said. “If a company does too good of a job advertising how consumer-friendly it is, the CFPB could use it as evidence against the company—in that it created this reasonable expectation that consumers can rely on the company.”

“It’s a really serious dilemma,” she said.

This conundrum may have ensnared Navient. “If borrowers are led to believe that calling their servicer is useless, who benefits?” Remondi said last year. “Help is a phone call away.”