Met Opera Suspends James Levine After New Sexual Abuse Accusations

By MICHAEL COOPER

The New York Times

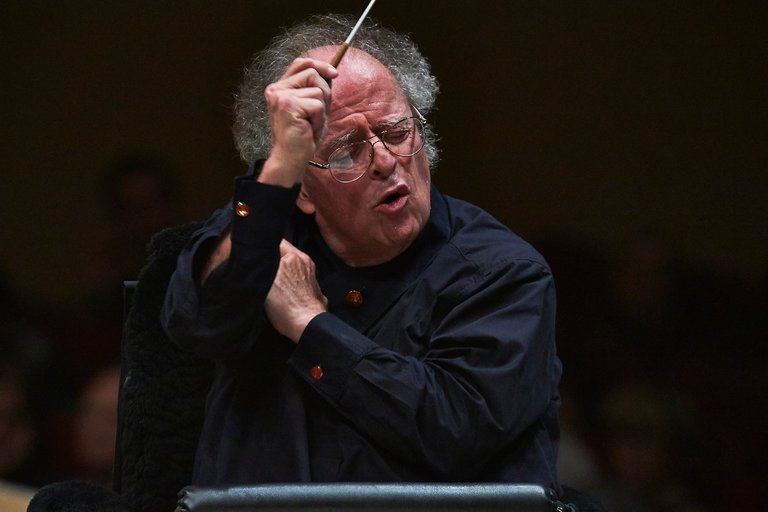

James Levine leading the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra at Carnegie Hall in 2016. Credit: Robert Altman for The New York Times

The Metropolitan Opera suspended James Levine, its revered conductor and former music director, on Sunday after three men came forward with accusations that Mr. Levine sexually abused them decades ago, when the men were teenagers.

Peter Gelb, the general manager of the Met, announced that the company was suspending its four-decade relationship with Mr. Levine, 74, and canceling his upcoming conducting engagements after learning from The New York Times on Sunday about the accounts of the three men, who described a series of similar sexual encounters beginning in the late 1960s. The Met has also asked an outside law firm to investigate Mr. Levine’s behavior.

“While we await the results of the investigation, based on these news reports the Met has made the decision to act now,” Mr. Gelb said in an interview, adding that the Met’s board supported his actions. “This is a tragedy for anyone whose life has been affected.”

The accusations of sexual misconduct stretch back to 1968.

Chris Brown, who played principal bass in the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra for more than three decades, said that Mr. Levine masturbated him that summer — and then coaxed him to reciprocate — when Mr. Brown was 17 at the Meadow Brook School of Music in Michigan. Mr. Levine, then 25, was a rising star on the summer program’s faculty. James Lestock said that Mr. Levine also masturbated him there that summer when Mr. Lestock was 17 and a cello student — the first of many sexual encounters with Mr. Levine that have haunted him. And Ashok Pai, who grew up in Illinois near the Ravinia Festival, where Mr. Levine was music director, said that he was sexually abused by Mr. Levine starting in the summer of 1986, when Mr. Pai was 16 — an accusation he made last year in a report to the Lake Forest Police Department in Illinois.

Ashok Pai on Sunday. He accused Mr. Levine of sexually abusing him for years, starting when Mr. Pai was 16. Credit: Karsten Moran for The New York Times

Ashok Pai on Sunday. He accused Mr. Levine of sexually abusing him for years, starting when Mr. Pai was 16. Credit: Karsten Moran for The New York Times

“I don’t know why it was so traumatic,” Mr. Brown, who is now 66, said in a recent interview at his home in St. Paul, fighting tears at the memory, which he said he was moved to share as part of the national reckoning over sexual misconduct. “I don’t know why I got so depressed. But it has to be because of what happened. And I care deeply for those who were also abused, all the people who were in that situation.”

Told of the accusations, a spokesman for Mr. Levine did not comment on Sunday night.

Speculation surrounding Mr. Levine’s private life has swirled in classical music circles for decades as he rose to a position of unprecedented prominence at the Met, leading more than 2,500 performances there. Though he stepped down as music director last year after a long struggle with health problems, Mr. Levine had been scheduled to lead a highly anticipated new production of Puccini’s “Tosca” starting New Year’s Eve and two other productions in coming months.

But now the Met — the nation’s largest performing arts organization and one of the world’s most prestigious opera houses — finds itself in the position that Hollywood studios, television networks and newsrooms have confronted in recent weeks, answering questions about what it knew about allegations of sexual misconduct against one of its stars, and what actions it did and did not take.

Mr. Gelb said allegations about Mr. Levine had reached the Met administration’s upper levels twice before, to his knowledge.

One was in 1979, when Anthony A. Bliss, who was then the Met’s executive director, wrote a letter to a board member about unspecified accusations about Mr. Levine that had been made in an unsigned letter.

“We do not believe there is any truth whatsoever to the charges,” Mr. Bliss wrote in the letter, a copy of which was obtained by The Times, which said the Met had spoken “extensively” with Mr. Levine and his manager. “Scurrilous rumors have been circulating for some months and have often been accompanied by other charges which we know for a fact are untrue.” (Mr. Bliss died in 1991, and the original, unsigned letter is unavailable, so the specific accusations against Mr. Levine in it remain unclear.)

DOCUMENT

1979 Metropolitan Opera Letter on Accusations About James Levine

Anthony A. Bliss, then executive director of the Met Opera, wrote this letter to a Met board member who had received anonymous accusations about James Levine, the music director at the time.

And then in October 2016, after Mr. Levine had stepped down from his position as music director, Mr. Gelb said he was contacted by a detective with the Lake Forest Police asking questions about Mr. Pai’s report.

Mr. Gelb said that he briefed the board’s leadership and that Mr. Levine denied the accusations. The company took no further action, waiting to see what the police determined. Then, on Saturday, the Met decided to investigate Mr. Levine after media inquiries about his behavior with young men.

Mr. Gelb said that the Met had appointed Robert J. Cleary, a partner at the Proskauer Rose law firm who was previously a United States attorney in New Jersey and Illinois, to lead its investigation.

Peter Gelb, the Metropolitan Opera’s general manager. Credit: Sara Krulwich/The New York Times

Peter Gelb, the Metropolitan Opera’s general manager. Credit: Sara Krulwich/The New York Times

The men coming forward now said that some of the abuse started years ago, at the beginning of Mr. Levine’s career, and that this sort of behavior had been widely rumored in music circles.

Mr. Brown, the former bass player in the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra, said that he had been surprised in the summer of 1968 when Mr. Levine made him principal bass at Meadow Brook, given that Mr. Brown was only 17 and had just finished his junior year of high school, while other players were older and more experienced. He said that he was initially flattered when Mr. Levine, the conductor of the school’s orchestra and the director of its orchestral institute, began to invite him to his dorm room late at night.

At their third meeting, Mr. Brown said, Mr. Levine began talking about sex.

“At that point I think it was basically a combination of fatigue and being young that allowed me to go to the bed — it was the bottom bunk — and have him masturbate me,” Mr. Brown said. “And then, almost immediately, he asked for reciprocation. And I have some very, very strong pictures in my memory, and one of them was being on the floor, and he was on the bottom bunk, and I put my hand on his penis, and I felt so ashamed.”

“The next morning I was late to rehearsal,” said Mr. Brown, who had been raised a Christian Scientist and recalled that he had received little sex education. “I was in a complete daze. Whatever happens when you get abused had happened, and it wasn’t just sexual.”

At their next meeting, Mr. Brown said, he told Mr. Levine that he would not repeat the sexual behavior, and asked if they could continue to make music as they had before.

“And he answered no,” Mr. Brown said, adding that Mr. Levine hardly looked at him for the rest of the summer, even while conducting him. “It was a terrible, terrible summer.” (That fall, after he returned for his senior year of high school, at the Interlochen Arts Academy, Mr. Brown told his roommate about Mr. Levine’s sexual advances at Meadow Brook, the roommate confirmed in an interview.)

James Lestock at his home in Asheville, N.C., on Sunday. He accused James Levine of sexual misconduct when Mr. Lestock was a teenager. Credit: Jacob Biba for The New York Times

James Lestock at his home in Asheville, N.C., on Sunday. He accused James Levine of sexual misconduct when Mr. Lestock was a teenager. Credit: Jacob Biba for The New York Times

Mr. Lestock, the teenage cello student at Meadow Brook, said in a telephone interview that he had a similar experience that summer in Mr. Levine’s dorm room.

“During the discussion, he suggested that I take my clothes off, because this would be natural and honest and expand my outlook on the world,” Mr. Lestock said. “My initial response included the word ‘no.’ I was not interested in that. But he ignored that, and pursued the point, and convinced me to let him masturbate me.”

Mr. Levine at that point was also an assistant conductor at the Cleveland Orchestra, and was surrounded by a tight-knit clique of musicians who were awed by him and followed him as his career took off. Mr. Lestock joined that group, whose members studied music together, traveled together, ate together, and sometimes lived together. But he said that over the years he was sometimes subjected to humiliating sexual encounters with Mr. Levine.

At one point in Cleveland, where he moved in 1969 to study at the Cleveland Institute of Music, he said that Mr. Levine encouraged the members of the group to put on blindfolds and masturbate partners they could not see. They did, Mr. Lestock said.

“This was the extent to which he had control,” Mr. Lestock said. Another member of the group, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to guard his privacy, said that he had also taken part in a blindfolded masturbation session.

A few years later, in a hotel near the Ravinia Festival, Mr. Lestock said that Mr. Levine caused him physical pain, telling him that he should “expand” his “range of emotions” and pinching him — repeatedly and hard — on his legs.

“Once I started to break down and cry, he continued to try to hurt me,” Mr. Lestock said of Mr. Levine, who was music director of Ravinia from 1973 through 1993.

But Mr. Lestock said he felt powerless to leave. “If I had left the group at the point, I would have had no career, no income, no friends, and have been totally alone in the world,” he said. After following Mr. Levine to New York in the early 1970s, Mr. Lestock, who is now 67, eventually left the group, and music.

Mr. Pai said that he first met Mr. Levine when he was four years old and his parents took him backstage after a Ravinia concert. In 1985, when Mr. Pai was 15, he said, Mr. Levine gave him a ride home and began holding his hand in an “incredibly sensual way.” The following summer, he said, Mr. Levine touched his penis in a hotel room near the festival, beginning what he described as years of sexual encounters.

“I was vulnerable,” said Mr. Pai, who is 48. “I was under this man’s sway, I saw him as a safe, protective person, he took advantage of me, he abused me and it has really messed me up.”

He said that the relationship continued for years and that his feelings were complicated: He shared a copy of a Western Union Mailgram he had sent to Mr. Levine at the Salzburg Festival in 1988 that contained the postscript “P.S. I love you.” But Mr. Pai came to realize that, in those early years, he had been too young to give consent.

Speculation about Mr. Levine’s private life has occasionally come into public view. In 1987, Mr. Levine dismissed talk of wrongdoing in an interview with The Times, saying that “both my friends and my enemies checked it out and to this day, I don’t have the faintest idea where those rumors came from or what purpose they served.”

A decade later, more rumors circulated in Germany, when politicians and media outlets debated his appointment to become the music director of the Munich Philharmonic, beginning in 1999. In an interview in The Times in 1998, Mr. Levine declined to respond to the speculation.

“I’ve never been able to speak in public generalities about my private life,” he said.

Officials at Ravinia, where Mr. Levine is scheduled to begin an ongoing annual residency next summer, said on Sunday that they first learned of the accusations through the media this weekend. “Ravinia finds these allegations very disturbing and contrary to its zero-tolerance policies and culture,” Allie Brightwell, its media manager, said in an email. “Ravinia will take any actions that it deems appropriate following the results of these investigations.”

The Boston Symphony Orchestra, which Mr. Levine led from 2004 through 2011, said in a statement Sunday that it had conducted “a personal and professional review of all aspects of James Levine’s candidacy” before naming him its music director, and that it had never been approached during his tenure with accusations of inappropriate behavior.

For the three men, unburdening themselves after decades has meant delving back into some of their most painful memories.

Sitting in his home in St. Paul, Mr. Brown looked over old documents from Meadow Brook, including a program for a starry concert performance of Verdi’s “Rigoletto” featuring Cornell MacNeil, Roberta Peters and Jan Peerce in which he played under Mr. Levine’s baton. He said his abuse had left scars for years.

A program for the Meadow Brook School of Music’s 1968 production of “Rigoletto.” Credit: Karsten Moran for The New York Times

A program for the Meadow Brook School of Music’s 1968 production of “Rigoletto.” Credit: Karsten Moran for The New York Times

“I’m still trying to figure out why it’s so incredibly emotional, and sticks with you for your whole life,” Mr. Brown said. “It’s shame, a lack of intimacy and sheltering yourself from other people.”